Berita Terkait

- Anggaran DPR RI Tahun 2016-2018

- Kehadiran Anggota DPR Pada Masa Sidang Ke-2 Tahun 2017-2018

- Review Kinerja DPR-RI Masa Sidang ke-2 Tahun 2017-2018

- Fokus DPR Masa Sidang ke-3 Thn 2017-2018

- Konsentrasi DPR Terhadap Fungsinya Pada Masa Sidang ke - 3 Tahun 2017 – 2018

- Kehadiran Anggota DPR RI Masa Sidang ke-3 Tahun 2017-2018

- Review Kinerja Masa Sidang Ke-3 Tahun 2017-2018

- Konsentrasi DPR Terhadap Fungsinya Pada Masa Sidang ke - 4 Tahun 2017– 2018

- Peristiwa Menarik Masa Sidang ke-4 Tahun 2017-2018 (Bidang Legislasi)

- Peristiwa Menarik Masa Sidang ke-4 Tahun 2017-2018 (Bidang Pengawasan)

- Peristiwa Menarik Masa Sidang ke-4 Tahun 2017-2018 (Bidang Keuangan, Lainnya)

- Review Kinerja DPR-RI Masa Sidang ke-4 Tahun 2017-2018

- (Tempo.co) Kasus Patrialis Akbar, KPPU: UU Peternakan Sarat Kepentingan

- (Tempo.co) Ini Proyek-proyek yang Disepakati Jokowi-PM Shinzo Abe

- (Tempo.co) RUU Pemilu, Ambang Batas Capres Dinilai Inkonstitusional

- (Media Indonesia) Peniadaan Ambang Batas Paling Adil

- (DetikNews) Besok Dirjen Pajak Panggil Google

- (Tempo.co) Aturan Komite Sekolah, Menteri Pendidikan: Bukan Mewajibkan Pungutan

- (Rakyat Merdeka) DPR BOLEH INTERVENSI KASUS HUKUM

- (Aktual.com) Sodorkan 4.000 Pulau ke Asing, Kenapa Pemerintah Tidak Menjaga Kedaulatan NKRI?

- (RimaNews) Pimpinan MPR dan DPR akan bertambah dua orang

- (Warta Ekonomi) Jonan Usulkan Kepada Kemenkeu Bea Ekspor Konsentrat 10 Persen

- (Tempo.co) Eko Patrio Dipanggil Polisi, Sebut Bom Panci Pengalihan Isu?

- (TigaPilarNews) DPR Harap Pemerintah Ajukan Banyak Obyek Baru untuk Cukai

- (Tempo.co) Menteri Nasir: Jumlah Jurnal Ilmiah Internasional Kita Meningkat

Kategori Berita

- News

- RUU Pilkada 2014

- MPR

- FollowDPR

- AirAsia QZ8501

- BBM & ESDM

- Polri-KPK

- APBN

- Freeport

- Prolegnas

- Konflik Golkar Kubu Ical-Agung Laksono

- ISIS

- Rangkuman

- TVRI-RRI

- RUU Tembakau

- PSSI

- Luar Negeri

- Olah Raga

- Keuangan & Perbankan

- Sosial

- Teknologi

- Desa

- Otonomi Daerah

- Paripurna

- Kode Etik & Kehormatan

- Budaya Film Seni

- BUMN

- Pendidikan

- Hukum

- Kesehatan

- RUU Larangan Minuman Beralkohol

- Pilkada Serentak

- Lingkungan Hidup

- Pangan

- Infrastruktur

- Kehutanan

- Pemerintah

- Ekonomi

- Pertanian & Perkebunan

- Transportasi & Perhubungan

- Pariwisata

- Agraria & Tata Ruang

- Reformasi Birokrasi

- RUU Prolegnas Prioritas 2015

- Tenaga Kerja

- Perikanan & Kelautan

- Investasi

- Pertahanan & Ketahanan

- Intelijen

- Komunikasi & Informatika

- Kepemiluan

- Kepolisian & Keamanan

- Kejaksaan & Pengadilan

- Pekerjaan Umum

- Perumahan Rakyat

- Meteorologi

- Perdagangan

- Perindustrian & Standarisasi Nasional

- Koperasi & UKM

- Agama

- Pemberdayaan Perempuan & Perlindungan Anak

- Kependudukan & Demografi

- Ekonomi Kreatif

- Perpustakaan

- Kinerja DPR

- Infografis

(Jakarta Globe) Indonesia refuses to reconsider impending executions

A new report by the International Narcotics Control Board, or INCB, has called on all countries to abolish the death penalty for drug-related crimes.

In the INCB’s annual report, which was published on Tuesday, board members encourage all “states which retain and continue to impose the death penalty for drug-related offenses to consider abolishing the death penalty.”

The INCB is an independent United Nations supervisory body, tasked with monitoring member states to ensure compliance with international drug treaties. Established in 1961, the INCB is made up of 13 elected representatives with expertise in either medicine or pharmacology, who are chosen once every five years by the UN’s Economic and Social Council.

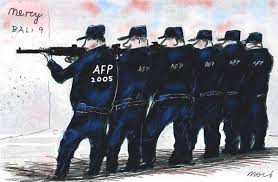

The release of the INCB’s latest report comes just days before the administration of President Joko Widodo is scheduled to execute 10 drug traffickers on Nusakambangan prison island. Among the convicts slated for execution are Australian citizens Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran, who arrived on the island under military escort on Wednesday morning.

The INCB’s report also coincides with the 58th annual meeting of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), which is scheduled to take place in Vienna next week. The commission is made up of 53 representatives from a cross section of member states, and is tasked with considering new policy measures on international drug control.

The issue of capital punishment is expected to be highlighted at next week’s CND meeting, following a highly publicized flurry of executions in Indonesia, many of which involve foreign nationals such as Chan and Sukumaran.

Indonesia’s policy of executing drug traffickers has provoked international condemnation from both human rights campaigners and foreign governments who believe capital punishment is an inhumane and ineffective way of combatting drug crime.

In January, Joko’s decision to execute a Dutchman and a Brazilian national sparked a diplomatic crisis in which the Netherlands and Brazil recalled their ambassadors from Jakarta. Another Brazilian and one French national are now among the 10 drug convicts scheduled for execution this month, with both governments threatening diplomatic sanctions should the executions go ahead.

Tensions between Indonesia and its close neighbor Australia are also set to escalate, after numerous requests to spare the lives of Chan and Sukumaran were rejected by Indonesia’s attorney general, H.M. Prasetyo. Australian Foreign Minister Julia Bishop attempted an eleventh-hour prisoner swap to spare Chan and Sukumaran from the firing squad, but this too, was flatly rejected.

A coalition of 11 human-rights groups and drug-policy think-tanks have also weighed in on Joko’s execution policy.

On Tuesday morning, following the launch of the INCB’s report, the coalition released a joint statement condemning the “recent spate of executions in Indonesia,” and also citing a “widening rift” between UN member states on the issue of capital punishment.

The joint statement — which has been signed by Reprieve, Harm Reduction International and the International Drug Policy Consortium — notes that “[a] number of other countries [in addition to Indonesia] have demonstrated a renewed enthusiasm for executing drug offenders over the past year.”

Iran, for instance, is believed to have executed more than 300 drug traffickers in 2014, and is thought to have executed 50 such convicts in January 2015 alone. Harm Reduction International believes that Iran has executed at least 10,000 drug convicts since the revolution of 1979, which represents the world’s highest per-capita execution rate on record.

Pakistan, a country that has previously considered ending capital punishment for drug offenses, has now returned to a policy of executing convicted drug traffickers.

In December 2014, the Pakistani government ended a six-year-moratorium on capital punishment, and now has at least 500 prisoners slated for execution in the coming months.

Among those 500, according to Tuesday’s joint statement, there are at least 112 drug traffickers who were apprehended with support and funding from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), an agency that officially opposes capital punishment for all drug offenses.

Oman, one of the few countries in the region that does not currently execute drug offenders, is also taking steps to introduce capital punishment.

In June 2014, the Omani State Council backed a proposal that would make drug trafficking a capital offense. The proposal is now being discussed at a “higher level” of government, according to Tuesday’s joint statement, “before being incorporated into [Omani] law.”

Amid this backdrop of growing polarization on the issue of capital punishment, UN member states will be keen to assert their position at the CND meeting slated for next week.

The timing of the INCB’s renewed call for all states to abolish capital punishment is crucial, since it reminds member states that the use of such provisions to combat drug crime runs counter to the will of the UN’s one and only independent supervisory body on drug control.

Having made its first statement condemning capital punishment only a year ago, the INCB is a late addition to the growing chorus of UN agencies and national governments calling for abolition.

After enduring decades of criticism for its failure to take an official stance on the death penalty, the INCB now stands shoulder-to-shoulder with a long list of UN authorities — including the secretary general, the UN Human Rights Committee and the UNODC — in its opposition to capital punishment.

Only time will tell, however, whether the growing consensus on the need to abolish the death penalty for drug offenses will translate into concrete policy changes at the level of each member state.

Rick Lines, executive director at Harm Reduction International, suggests the UN should cut funding to those states that continue to execute drug traffickers, as a form of leverage in the battle for abolition.

“The first step must surely be for the UN to refuse to fund anti-drug operations in states which maintain the death penalty for drug offenses,” Lines said in Tuesday’s joint statement, “and instead use this money to tackle the health, social and human rights impacts of drug use.”

The impact of any such outside pressure remains in doubt, however, given that President Joko’s mantra of “no compromise” has proved to be immensely popular among conservative voters.